Something happened in early 2020 that made me step back from everything digital. Maybe it was the sudden shift to online everything, or maybe I just got tired of the noise. Whatever it was, I deleted my social media accounts and stayed away for almost two years. Not just Instagram—I barely even answered phone calls.

It wasn’t intentional at first. I just found myself choosing books over screens, walks over scrolling, actual conversations over commenting on posts. Life felt quieter, slower, more mine.

When I started using Instagram again in October 2022, it was different. Minimal. A photo every few months, maybe a story here and there. I posted when something felt worth sharing, not because I felt compelled to share.

When I started my PhD in neuroscience in August 2023, this digital minimalism became a research problem. I’d settled on studying problematic digital behavior—the compulsive, consuming relationship millions develop with their devices. But I’d never experienced what I was studying.

The Research Gap

In anthropology, there’s this concept called “going native.” It happens when researchers studying a culture become so immersed that they lose their analytical distance. They stop observing from the outside and start living from the inside. Traditionally, it’s seen as a methodological failure—you’re supposed to maintain objectivity, not become what you’re studying.

But I kept thinking: what if that distance is exactly the problem?

The literature on problematic digital behavior is full of brain scans, behavioral surveys, and statistical correlations. We can measure dopamine responses, track usage patterns, identify risk factors. But there’s something missing in all this data—the actual experience of losing control to a screen.

What does it feel like when checking your phone stops being a choice and becomes a compulsion? When does scrolling shift from entertainment to something you can’t stop doing? How does it feel in your body when you can’t access your device? These aren’t questions you can answer with fMRI scans or questionnaires.

I realised I was trying to understand a fundamentally experiential phenomenon from the outside. It’s like studying love by measuring heart rates, or understanding music by analyzing sound waves. The data tells you something, but it misses the essence—the lived reality of what it’s actually like.

Phenomenology argues that lived experience is a valid form of knowledge. That sometimes the only way to understand something is to be inside it. Not just observing the behaviors of digital addiction, but feeling the pull, the compulsion, the gradual loss of agency.

So I started wondering: what if I deliberately went native? What if I temporarily gave up my researcher’s distance and allowed myself to experience what millions of people experience every day? Could I learn something that no amount of external observation could teach me?

It felt risky—both professionally and personally. But the more I thought about it, the more necessary it seemed. How can you help people escape something you’ve never been trapped by?

The Experiment

In April 2025, I decided to find out. Not as a formal experiment with protocols and controls, but as a deliberate shift in how I engaged with digital spaces. I would stop being so conscious about my usage. Stop setting boundaries. Stop analyzing every interaction.

I would let Instagram—and whatever apps came with it—have more space in my life. I’d post more, scroll more, engage more. I’d let myself develop whatever relationship wanted to develop, without my usual guardrails.

Looking back, I thought I was setting up an experiment. But experiments have endpoints. What I was really doing was much simpler and more dangerous: I was giving up control.

The Conscious Descent

I gave myself permission to autopilot into digital engagement through unexamined choices. No more conscious consumption. No more deliberate limits. I wanted to experience what happens when someone like me—aware of the mechanisms, educated about the risks—simply lets go.

The transformation was swift and unsettling.

The Honeymoon

It started innocuously. My phone migrated from my study table to my bedside table. Then it became the first thing I reached for each morning—before my feet hit the floor, before acknowledging the physical world. The bright rectangle pulled me in with promises of connection and novelty.

Five minutes became twenty. Twenty became an hour. Sometimes I’d watch gym videos in bed instead of actually going to the gym. Here’s the strange part: those videos gave me a similar dopamine spike to actual exercise. My brain couldn’t distinguish between watching someone deadlift and doing it myself. I felt productive while being completely passive.

The Automatic Hand

My hand developed its own intelligence. Struggling to understand a complex neural network architecture? Hand reaches for phone. Waiting for code to run in the lab? Phone. Standing in line at the campus cafeteria ? Phone.

I caught myself scrolling Instagram while trying to focus on a challenging research paper—right there in the computational neuroscience lab. The embarrassment wasn’t enough to stop me. The pull was stronger than academic focus.

Every gap in my day became a “compulsive scroll zone.” Queue for lunch at the research center, bathroom breaks between task designing, those few minutes waiting for the codes to be executed. The spaces that once allowed for mental processing, reflection, or simply letting thoughts settle were consumed by the need to consume.

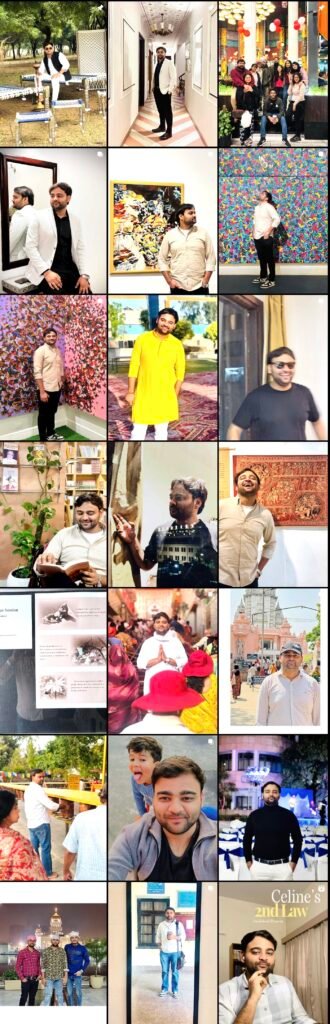

In one month, I posted over 50 pictures Link . Seventy. I’d never posted that much in my entire life combined.

The Hunger for Validation

At first, posting felt natural. A photo here, a story there. The likes were nice—a small acknowledgment from friends and colleagues. But gradually, something shifted. The likes became necessary, not just nice.

I started posting more frequently, craving that little spark of validation each notification brought. Any buzz from my phone would send a small jolt of excitement through me—maybe someone had liked my latest post, maybe there was a comment to read. The anticipation became physical: tight chest, restless fingers, a gnawing sense that something was incomplete until I checked.

When the notifications stopped coming, something inside me would drop. A sadness I couldn’t locate. An agitation that felt like hunger, but worse—because at least when you’re hungry, you know what you need.

Not being able to check created genuine anxiety. A persistent unease, like forgetting something important but being unable to remember what

The Algorithm’s Perfect Trap

Instagram learned me faster than I learned myself. Within days, it knew I was interested in neuroscience research, AI developments, philosophy debates, psychology insights. The algorithm became my dealer, serving exactly what would keep me scrolling.

But here’s what’s insidious about personalised feeds: they don’t just show you what you like—they amplify whatever keeps you watching. My genuine interest in consciousness research became endless rabbit holes about the hard problem of consciousness. My curiosity about startups became a comparison trap. My appreciation for culture became a source of inadequacy. My fascination with philosophical debates became a source of inadequacy about my own intellectual depth.

The reels were the worst. They’d trigger memories—some good, some painful—then immediately distract me before I could process them. To calm the chaos in my head, I’d need more reels. It was like scratching an itch that only got worse with scratching.

Performance Mode

When I was with friends, I wasn’t really present. Half my mind was composing captions for moments that hadn’t even finished happening yet. During conversations, I’d find myself thinking: “This would make a good story” or “What song would work with this?”

I’d spend embarrassing amounts of time choosing the right music for posts—sometimes an hour scrolling through options for a 15-second story. The caption became more important than the moment it was supposed to capture. I’d craft and re-craft text, trying different approaches, varying the tone, wondering what would get the most engagement.

Even in genuine moments of connection or discovery, there was this secondary layer of consciousness evaluating everything for its social media potential. I wasn’t just living experiences—I was curating them, packaging them, optimizing them for an audience.

In theory, I was sharing my research journey and insights. In reality, I was performing a version of myself that felt increasingly distant from who I actually was.

What It Stole

Instagram took my curiosity first. I used to love diving deep into new technologies, working on creative projects, learning for the pure joy of discovery. That stopped. Why think when you can scroll?

Then it took my focus. Reading academic papers became nearly impossible. My mind, accustomed to rapid stimulation, couldn’t settle into the slower rhythm of deep thought. My attention span fragmented to match the length of a reel.

It took my body awareness too. Instead of listening to what I actually needed, I was constantly consuming marketing. Supplements, workout routines, lifestyle upgrades. I stopped asking what my body wanted and started asking what other people were selling.

It even invaded my dreams. Literally. I’d dream about scrolling feeds, about notifications, about likes. My sleep became another battleground for attention.

The Dopamine Drought

The scariest part was how normal life became understimulating. A good meal wasn’t enough—I needed to eat while watching something. A walk wasn’t enough—I needed podcasts and music. A conversation wasn’t enough—I needed my phone nearby.

When did you last eat a meal and that was all you were doing? No phone, no TV, no background stimulation? Try it. You’ll probably think, “I should do this more often.” Then you won’t do it again for weeks.

That’s what Instagram did to me. It made reality feel insufficient.

The Death of Boredom

Every quiet moment felt dangerous. Boredom became the enemy—a space where difficult thoughts might surface, where I might have to face whatever I was avoiding. So I filled every gap with stimulation.

But I think I had it backwards. Boredom isn’t the enemy of curiosity—it’s curiosity asking for help. Those empty moments aren’t problems to solve with content consumption. They’re invitations to create, to think, to wonder.

All those hours I spent finding “funny memes,” I could have been sketching, writing, inventing. Being bad at drawing would have fed my curiosity more than being good at finding viral content.

The Warning Signs (Going Native)

After about a month, something fundamental had shifted. What started as a research experiment had quietly become something else entirely. I was no longer studying problematic digital behavior—I was living it.

The signs crept up gradually, then hit me all at once:

My hand had developed its own mind – I’d reach for my phone before consciously deciding to check it. The motion had become as automatic as breathing. Sometimes I’d find myself holding it without any memory of picking it up.

My attention was no longer mine – Even during important lab meetings or deep conversations, part of my mind was elsewhere, wondering about notifications. Digital thoughts would intrude on physical moments like background noise I couldn’t turn off.

Separation anxiety became real – Being away from my device created genuine discomfort. Not just boredom, but an actual physical unease. A persistent feeling that I was missing something critical, though I could never articulate what.

Nothing else felt stimulating enough – My post-dinner reading sessions, once a cherished ritual, became impossible. I’d pick up a research paper or book, read a paragraph, then find myself reaching for my phone. The slow reward of deep reading couldn’t compete with the instant hits of scrolling.

Everything became content – I started viewing experiences through the lens of shareability rather than personal meaning. A beautiful sunset wasn’t just beautiful—it was a story opportunity. A conversation with a colleague wasn’t just interesting—it was potential post material.

Sleep became negotiable – My phone became both the last thing I saw at night and the first thing I reached for in the morning. Those quiet moments before sleep, once time for reflection or planning, were filled with one more scroll, one more check.

My willpower evaporated – I’d set limits—”only 30 minutes today”—then consistently break them. The gap between what I intended to do and what I actually did was alarming and demoralizing.

Most disturbing was the exhaustion. After hours of scrolling, I’d feel drained in a way that made no sense. I hadn’t done anything physically demanding, yet I’d feel as tired as after a long day in the lab. It was like my mental energy had been siphoned away, leaving me depleted and somehow empty.

This is when I knew I’d gone native. I was no longer the researcher observing from outside—I was the subject, trapped inside the very phenomenon I’d set out to understand. The analytical distance I’d planned to maintain had collapsed entirely.

What the Science Tells Us (In Plain Terms)

Coming out of this experience, I can see why these platforms are so effective at capturing attention. They’re not accidentally addictive—they’re professionally addictive, designed using principles from behavioral psychology.

The Dopamine Trap: When I posted something, I could literally feel my brain waiting for the reward. That tight chest feeling I described? That’s your dopamine system in overdrive. Our brains evolved to seek rewards that helped us survive—food, social connection, new information. Social media hijacks this system with variable reward schedules. You never know when you’ll get a like or find something interesting, so your brain stays in anticipatory tension. It’s the same mechanism that makes gambling addictive, except your phone is always in your pocket.

The Infinite Scroll: I’d tell myself “just one more scroll” hundreds of times in a session. There was never a natural place to stop—no chapter ending, no credits rolling. Unlike a book or TV show, social media feeds deliberately remove all exit ramps. You have to actively decide to stop, which requires breaking the flow state that makes scrolling feel so effortless. The platform wins every time you have to make that decision.

Social Reciprocity Weapons: This one hit me hard. When someone viewed my story, I felt genuinely compelled to view theirs back. Messages created pressure for immediate responses. Likes generated obligations to reciprocate. These apps weaponize the social norms that evolved to build communities—except now they’re being used to extract engagement from you.

Attention Fragmentation: I could actually feel my tolerance building. Things that used to capture my attention for hours—research papers, deep conversations—started feeling slow and understimulating. My brain was literally being rewired to crave rapid-fire stimulation. After weeks of scrolling, single-focus activities felt insufficient. Your attention span literally shrinks to match the content format.

Time Distortion: Hours felt like minutes when I was scrolling, but afterward, I couldn’t remember what I’d actually seen. This isn’t just about losing track of time—it’s about how rapid content consumption bypasses normal memory formation. You experience the time but don’t really remember it, leaving you with a sense of lost hours and nothing to show for them.

The Illusion of Choice: What felt like free will was actually behavior shaped by sophisticated design. Every notification, autoplay feature, and algorithmic feed—these aren’t conveniences. They’re interventions in your decision-making process, designed by teams who understand your psychology better than you do.

The Neuroscience Behind the Pull

During my month of heavy usage, I could feel my brain changing. The need for stimulation increased while satisfaction from simple pleasures decreased. When I spent an hour choosing music for a 15-second story, that wasn’t just perfectionism—that was my reward system demanding more intensity to feel satisfied.

This matches what researchers find in brain imaging studies: heavy social media use alters the same neural pathways involved in substance addiction. The prefrontal cortex—responsible for self-control and long-term thinking—shows decreased activity, while the reward system becomes hyperactive and then gradually less sensitive. You need more stimulation to feel normal, and you have less capacity to resist the urge to seek it.

For people my age (I’m 25), this is particularly concerning. Our brains are still developing impulse control while our reward systems are fully mature. We’re biologically vulnerable to these influences in ways that older adults aren’t. The platforms know this.

What I Know Now

This experience fundamentally changed how I understand problematic digital behavior. Most research treats it as individual pathology—measuring brain differences, identifying risk factors, developing interventions targeting personal behavior.

This experience taught me that attention is the most valuable resource we have. And I learned how easily we trade it away for the illusion of connection and productivity.

I learned that these platforms aren’t neutral tools—they’re environments designed to extract engagement. Individual willpower is no match for systems optimized by teams of engineers and behavioral scientists who’ve studied exactly how to bypass your conscious decision-making.

I learned that addiction isn’t about moral failure or lack of discipline. It’s about human psychology meeting environments specifically designed to exploit it.

Most importantly, I learned that awareness alone isn’t protection. Even as a neuroscience researcher studying this exact phenomenon, I fell into the same patterns as everyone else. Knowledge without boundaries is just intellectual decoration.

How to Pilot Your Way Out

You autopilot your way into digital addiction through unexamined choices. You pilot your way out through examined ones.

What Doesn’t Work First:

- Digital detox apps (you can just delete them or override the limits)

- Willpower alone (you’re fighting a system designed by professionals)

- Going cold turkey without replacement activities (you’ll just binge later)

What Actually Works:

Add Physical Friction: I moved my phone charger to another room—that extra 30 seconds was often enough to break the impulse. Delete apps from your phone entirely. Disable all non-essential notifications. Those tiny spaces between wanting to check and actually checking? That’s where choice lives.

Replace, Don’t Just Restrict: Find other sources for what social media provides—social connection, entertainment, information. I started calling friends instead of scrolling their updates. Digital fasting only works if you fill the space with something meaningful.

Listen to Boredom: Instead of immediately medicating quiet moments with stimulation, sit with them. Your mind will tell you what it actually wants to explore. Some of my best research ideas came back when I stopped filling every gap with content.

Design Your Environment: Your surroundings shape your behavior more than your willpower does. Make healthy choices easier and unhealthy ones harder. I put books where my phone used to be.

Practice Single-Focus Activities: Eat without screens. Walk without podcasts. Have conversations without phones nearby. Rebuild your capacity for sustained attention—it’s like rebuilding muscle after an injury.

A Personal Note

If you’re reading this and recognising yourself, you’re not broken. You’re human, responding normally to systems designed to capture your attention. The solution isn’t more willpower—it’s better boundaries.

I still use Instagram sometimes, but consciously, with intentional friction and clear limits. I have to consciously log in each time. The difference is night and day. Instead of being used by the platform, I use it—briefly, purposefully, then close it and return to life.

The moment I knew I had to step back was when I caught myself crafting captions during a meaningful conversation with a friend. I wasn’t present for my own life—I was performing it.

Your attention is under attack by some of the smartest people on earth, using billion-dollar algorithms designed specifically to capture it. But it’s still yours to defend.